Recent research has successfully mapped the drainage systems on Mars, revealing critical insights into the planet’s watery past. Conducted by a team from the University of Texas at Austin, this study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, aims to enhance our understanding of ancient Martian river basins and the volume of water that once flowed on the planet.

The researchers utilized data from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) and the Context Camera (CTX), both of which have provided extensive imagery of the Martian surface. MOLA was integral to NASA’s Mars Global Surveyor mission, operational from 1997 to 2006, while CTX is currently orbiting Mars aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. The CTX has the unique advantage of offering complete coverage of the Red Planet.

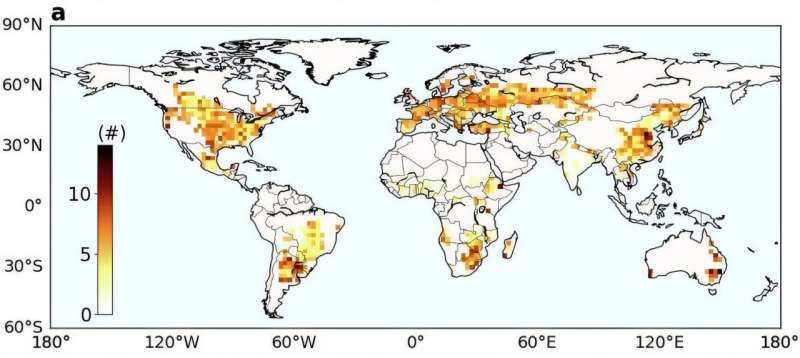

To identify and categorize the river systems, the team employed ArcGIS Pro, a mapping software suited for planetary data. They focused on drainage systems larger than 10,000 km², a standard benchmark for significant drainage areas on Earth. Ultimately, the researchers mapped 16 drainage systems, estimating they transported approximately 28,000 km³ of sediment, or about 42 percent of the total sediment volume believed to have flowed on ancient Mars.

The study further revealed that outlet canyons contributed around 24 percent of the global river sediment volume on Mars. This finding adds to the growing body of evidence indicating that Mars once had liquid water, which is crucial for understanding the planet’s geological history.

Mars is estimated to have formed approximately 4.5 billion years ago, and while the scientific community debates the duration of its liquid water presence, a 2022 study suggested that Mars had liquid water as recently as 2 billion years ago. Alongside river systems, geomorphological features such as deltas, outflow channels, and coastal-like terraces provide further evidence of Mars’ hydrological past.

Mineralogical findings, including clays, sulfates, carbonates, and hematite—informally known as “blueberries” after being discovered by NASA’s Opportunity rover in 2004—also indicate the historical presence of water. Scientists propose several theories regarding the loss of water on Mars, including the decline of its magnetic field, climate change, and geological processes that may have buried water.

The magnetic field of Mars, which was once strong, diminished due to a smaller core compared to Earth. This led to increased exposure to solar and cosmic radiation, which stripped the surface and atmosphere of water. While some water has escaped into space, models suggest that other portions could have become groundwater, potentially stored in the polar regions.

As research continues, scientists remain hopeful that further studies will provide deeper insights into the ancient river basins of Mars and the implications for understanding its climate history. The mapping of these watershed systems represents a significant advancement in planetary science and sets the stage for future exploration of not only Mars but also other celestial bodies.

The findings from this study underscore the importance of ongoing research in unraveling the mysteries of our solar system and the history of water on planets beyond Earth.