Robots utilizing spinning masses can roll, swim, and potentially achieve insect-like flight, according to research conducted at Clemson University. Led by mechanical engineering professor Phanindra Tallapragada, this innovative approach relies on centripetal force to generate motion, moving away from traditional robotic designs that depend on motors and joints.

The robots showcase a range of movements. For instance, a bright orange wheel rolls across a concrete surface before jumping into the air as if defying gravity. Nearby, another robot mimics aquatic life, swimming through water with fluid motions, while a third navigates through narrow pipes with ease. These diverse capabilities all stem from the same fundamental physical principle: an off-center mass spins rapidly to create forces that can push, lift, or twist the robots’ bodies.

Tallapragada emphasizes that these robots illustrate mathematical concepts in action rather than mere machines filled with complicated components. He stated, “A lot of robotics today is perceived as designing something with motors, microcontrollers, machine learning, and AI—less importance is given to the dynamics and math, at least in the public perception.”

Multiple Functionality from Spinning Masses

A notable creation from Tallapragada’s lab is the remote-controlled robot known as the Spin Gyro. This device can jump when its internal mass rotates sufficiently to lift it off the ground. Unlike conventional spring-based jumpers, the Spin Gyro can repeat its jumping motion almost instantaneously, making it particularly effective on rough or uneven terrain.

Another remarkable robot developed in the lab resembles a fish. It swims by transferring energy from a spinning mass to its tail, allowing it to dive, turn, and propel itself forward. This system is not only efficient but also holds potential for applications in environmental monitoring, such as assessing water quality in lakes and oceans.

Additionally, the team has designed a robot capable of crawling through tight pipes by utilizing a spinning mass that causes bristles on its surface to compress and release rapidly. This friction with the pipe walls enables the robot to advance through spaces as narrow as one inch, making it ideal for inspecting ducts, gas lines, or facilitating cable installations across extensive pipe networks.

Graduate students and postdoctoral researchers play a vital role in these projects. Prashanth Chivkula, a graduate student involved in the development of the swimming robot, expressed his commitment, stating, “I want to be a roboticist, and that’s what motivates me every day—to make robots that do something useful in the world.”

Expanding into the Air

The team is currently exploring the application of this spinning mass technology for aerial robotics. Tallapragada has initiated a project aimed at creating insect-inspired flying robots. Instead of relying on traditional motors, these flying devices will use spinning masses to drive wings at the high frequencies necessary for flight similar to that of insects. This ambitious project is backed by a three-year grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation.

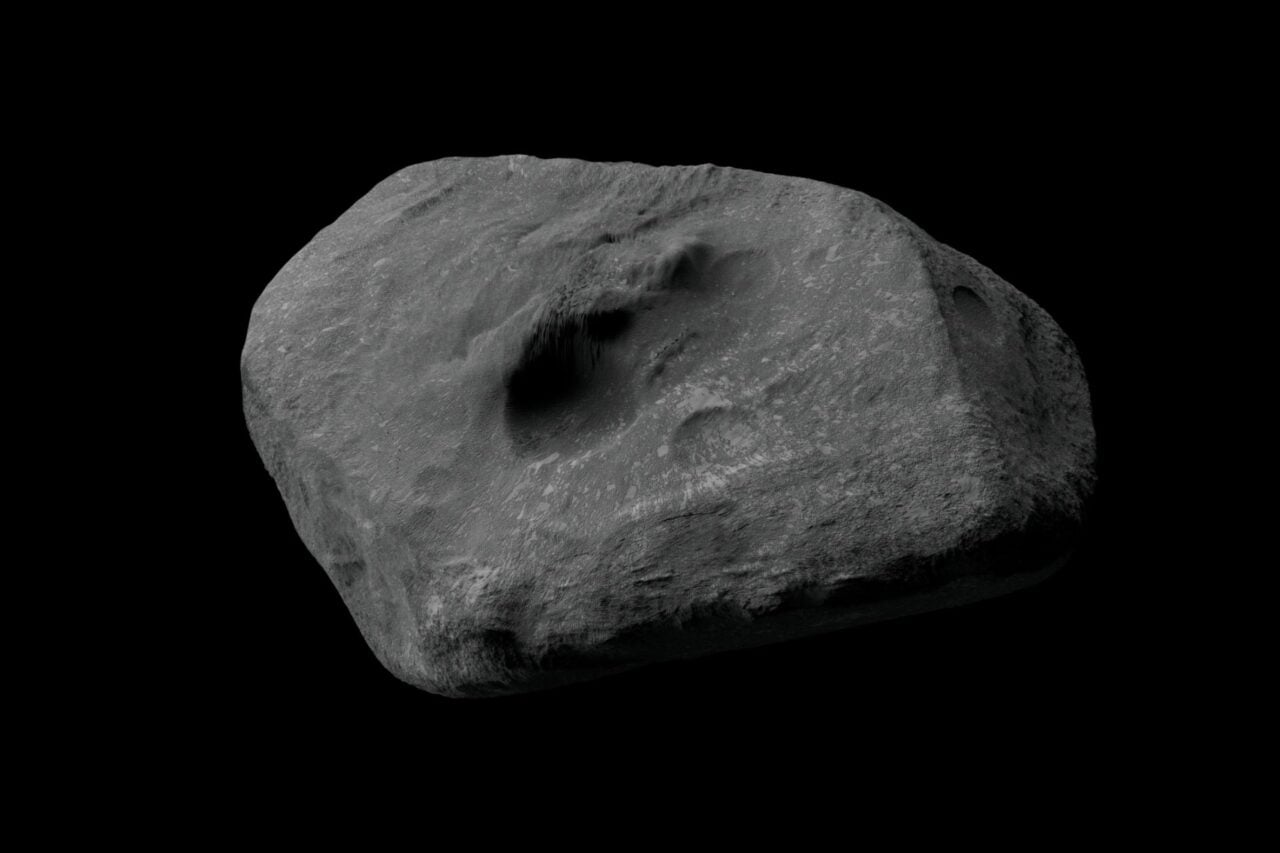

Tallapragada envisions broader implications for this technology, suggesting that a robot capable of rolling, jumping, swimming, and flying could be instrumental in planetary exploration. Such a versatile machine could traverse icy surfaces, leap through vents, and dive beneath frozen crusts on distant moons in search of liquid water.

Expressing his enthusiasm for innovation, Tallapragada remarked, “I just like working on these new ideas that are very different from what others are doing and seeing them come to physical action. Once they come into action, that gives me more motivation to go back to the whiteboard and come up with more models.”

This research represents a significant advancement in the field of robotics, showcasing how alternative motion principles can lead to the development of multifunctional machines with numerous potential applications.