On November 1, 1995, a groundbreaking discovery in astronomy emerged when Swiss scientists Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz announced the identification of the first planet orbiting a sun-like star, a significant milestone in the search for extraterrestrial life. The discovery took place at the Haute-Provence Observatory in France, where the researchers had been conducting extensive observations of a star named 51 Pegasi, located approximately 50 light-years from Earth.

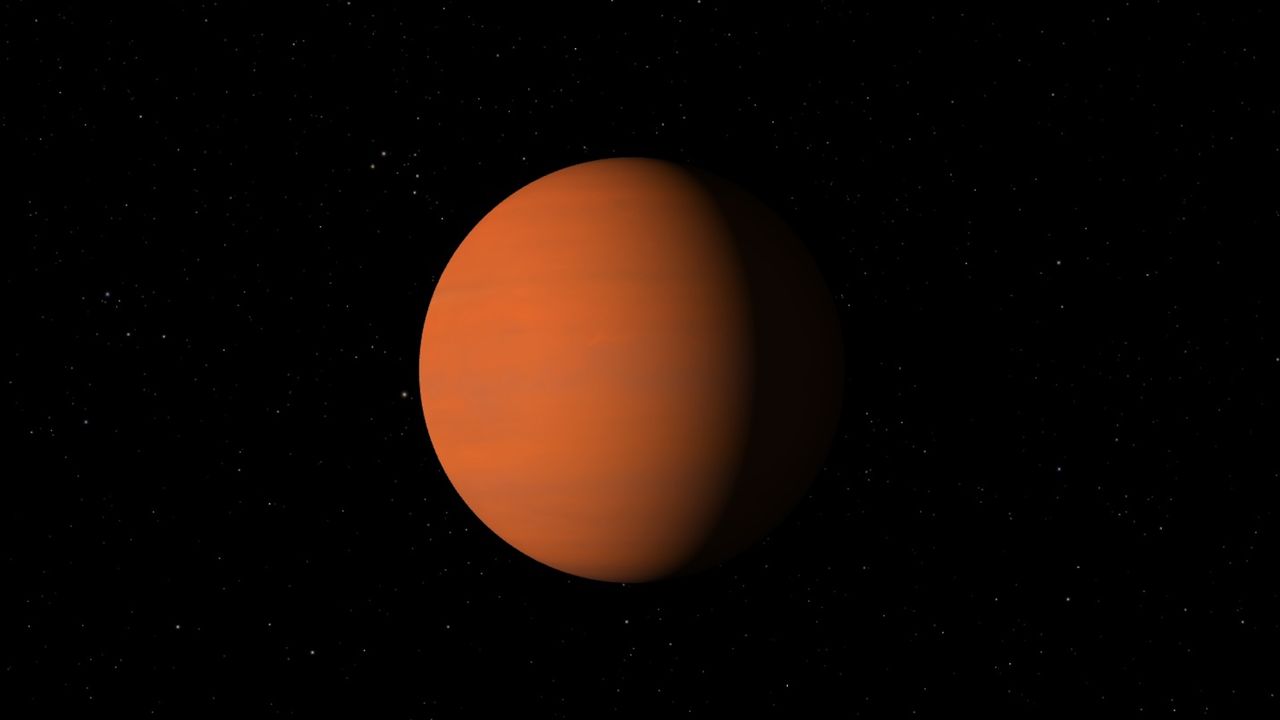

The pair of astronomers had spent 18 months scrutinizing the light and movement of nearly 150 stars to uncover anomalies indicating the presence of a planet. Their efforts culminated in the detection of a “hot Jupiter,” dubbed 51 Pegasi b or Dimidium. This gas giant, larger in diameter than Jupiter, orbits its star at a remarkably close distance of just 5 million miles (8 million kilometers), completing a revolution every 4.2 days.

The significance of this discovery extended far beyond the identification of a single planet. It marked the birth of the field of exoplanet research, opening doors to a new understanding of the universe and humanity’s place within it. Prior to this, astronomers primarily focused on detecting signals from intelligent life, a pursuit that began as early as the 1960s. However, by the 1980s, the approach shifted towards analyzing the light emitted by stars to identify potentially habitable planets.

Despite earlier attempts to identify planets around distant stars, including a Canadian team’s research in 1987 that ultimately led to confirmation years later, Mayor and Queloz’s findings represented a pivotal advancement. Their observations suggested that the star’s wobble was caused by the gravitational influence of an orbiting planet, a groundbreaking revelation in planetary science.

Impact on Exoplanet Discovery and Future Research

Following their announcement, the scientific community quickly validated Mayor and Queloz’s findings, with astronomers from the Lick Observatory in California confirming the presence of Dimidium. The publication in the journal Nature not only solidified their discovery but also ignited a flurry of interest in the search for exoplanets. Within the subsequent years, dozens of exoplanets were detected, leading to the development of novel techniques for identifying these distant worlds.

The impact of their work has been profound. By 2004, astronomers using the Very Large Telescope in Chile captured the first photographic evidence of an exoplanet, further expanding the boundaries of astronomical research. Today, astronomers have identified at least 6,000 exoplanets, although none has yet been confirmed to harbor life. Nevertheless, the ongoing exploration of these distant worlds continues to reveal promising candidates for potential habitability.

In recognition of their groundbreaking contributions to astronomy, Mayor and Queloz were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2019, sharing the honor with Canadian physicist James Peebles. Their work has not only changed the landscape of planetary science but has also inspired future generations of scientists to explore the cosmos.

As the field of exoplanet research continues to evolve, astronomers remain hopeful of discovering planets that could support life, further fueling humanity’s quest to understand our place in the universe. With each new discovery, the dream of finding extraterrestrial life inches closer to reality, showcasing the enduring spirit of scientific inquiry.