Kelp cultivation faces significant challenges due to rising seawater temperatures linked to global warming. A research team at the Chinese Academy of Sciences has developed a novel method for breeding heat-resistant kelp cultivars, which could transform the seaweed farming industry. This breakthrough, led by Prof. Shan Tifeng from the Institute of Oceanology, was published in the Journal of Phycology on November 19, 2025.

Kelp species, particularly Saccharina japonica and Undaria pinnatifida, are vital economic resources worldwide. However, the impact of climate change is prompting researchers to seek new, adaptable cultivars that can withstand warmer waters. Traditional breeding methods, particularly triploid breeding, have not been effectively applied to seaweeds until now.

The study introduces a method for creating triploid kelp cultivars by utilizing a process that has been successful in terrestrial crops but rarely seen in marine environments. Historically, obtaining diploid gametophytes from heterozygous sporophytes through apospory presented challenges due to the unpredictable sex of the gametophytes. This inconsistency hindered researchers’ ability to conduct precise crossings necessary for developing triploid lines.

Prof. Shan states, “This issue has become the primary technical bottleneck limiting triploid breeding in kelp.” To overcome this, the research team focused on generating homozygous diploid gametophytes by inducing apospory in doubled haploid (DH) sporophytes of Undaria pinnatifida. They then crossed these with haploid gametophytes to produce robust triploid sporophytes.

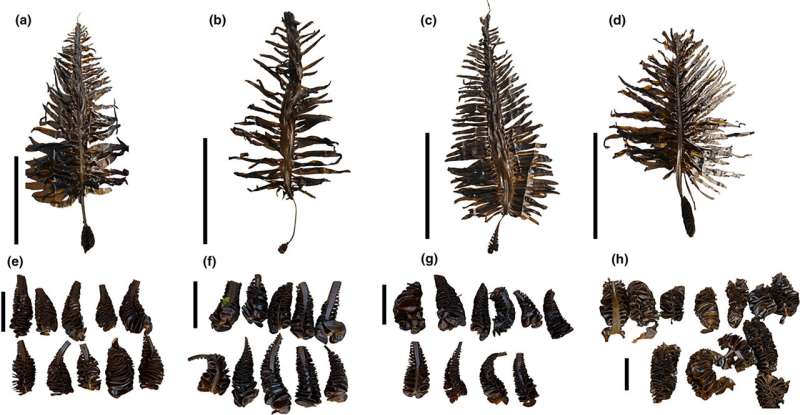

The innovative approach involved several steps. First, DH sporophytes were created through selfing a monoicous gametophyte. This led to the derivation of single-sex (male) diploid gametophytes via apospory. Subsequently, these male gametophytes were crossed with three female haploid gametophyte clonal lines, resulting in three successful triploid hybrid lines.

Cultivation trials conducted at a seaweed farm demonstrated that these triploid hybrids outperformed conventional diploid cultivars across several metrics. The hybrids exhibited a faster growth rate, longer blades, enhanced resistance to high temperatures and aging, and a notable characteristic of sterility. Such traits are crucial for the resilience of kelp in a changing climate.

Prof. Shan further asserts, “The triploid breeding method established in this study may also be applicable to other kelp species, as they share a similar life cycle.” This research not only addresses immediate agricultural needs but also provides a practical polyploid breeding tool for kelp, supporting the long-term stability and development of the seaweed farming industry.

As global temperatures continue to rise, initiatives like this one are essential for the sustainability of marine agriculture. The advancement of heat-resistant kelp cultivars could pave the way for stronger, more adaptable seaweed farming practices, vital for both economies and ecosystems worldwide.

For further details, refer to the full study by Tifeng Shan et al in the Journal of Phycology (DOI: 10.1111/jpy.70107).