A study conducted by biologists at Dartmouth University has revealed significant insights into how embryos transition during early development. Published in EMBO Reports, the research focuses on how embryos, specifically using Drosophila or fruit flies as a model, determine when to reorganize their DNA and activate their genes. This understanding could pave the way for further research into similar mechanisms in humans.

According to Amanda Amodeo, an assistant professor of biological sciences and the senior author of the study, the DNA packaging within early embryos undergoes remarkable changes. “The way that the DNA is packaged changes pretty dramatically in the very early embryo, as it goes from maternal control to transcribing its own genes,” she stated. This transition is closely linked to the embryo’s nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, a factor that may have implications for understanding certain cancers and aging processes in humans.

Research on fruit flies is particularly advantageous due to their genetic tractability and the transparency of their embryos, which allows for detailed imaging. The tiny eggs develop within a 24-hour timeframe, providing a rapid model for studying embryonic development. Amodeo noted the historical significance of Drosophila in identifying fundamental biological processes relevant to both human and animal health.

Early embryo development relies heavily on proteins inherited from the mother. These maternal proteins facilitate critical processes before the embryo begins to synthesize its own proteins. After approximately 13 rounds of rapid cell division, the embryo shifts control of its development. At this stage, a single nucleus has multiplied into over 6,000 nuclei.

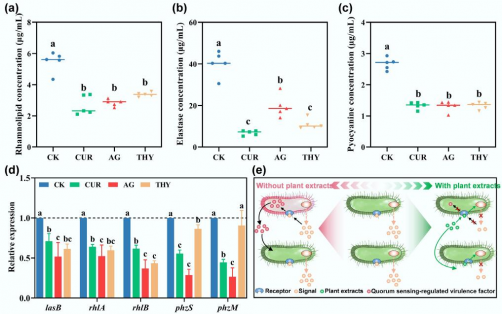

Amodeo and her team investigated the role of histones, specifically the histone variant H3.3, in this pivotal transition. Histones are proteins that help package DNA, ensuring it remains organized and protected. Previous studies have established that specific histones are associated with gene activation in adult cells, but their function in embryonic development was less understood.

The research demonstrated that as the fruit fly embryo undergoes cell division, there is a notable switch from histone H3 to H3.3, which occurs when the embryo detects a high concentration of nuclei. “Even though they only differ by four amino acids, H3 and H3.3 have very different functions,” explained Anusha Bhatt, a graduate student in Amodeo’s lab and the lead author of the paper. H3 is primarily used for DNA replication, whereas H3.3 is involved in activating specific genes.

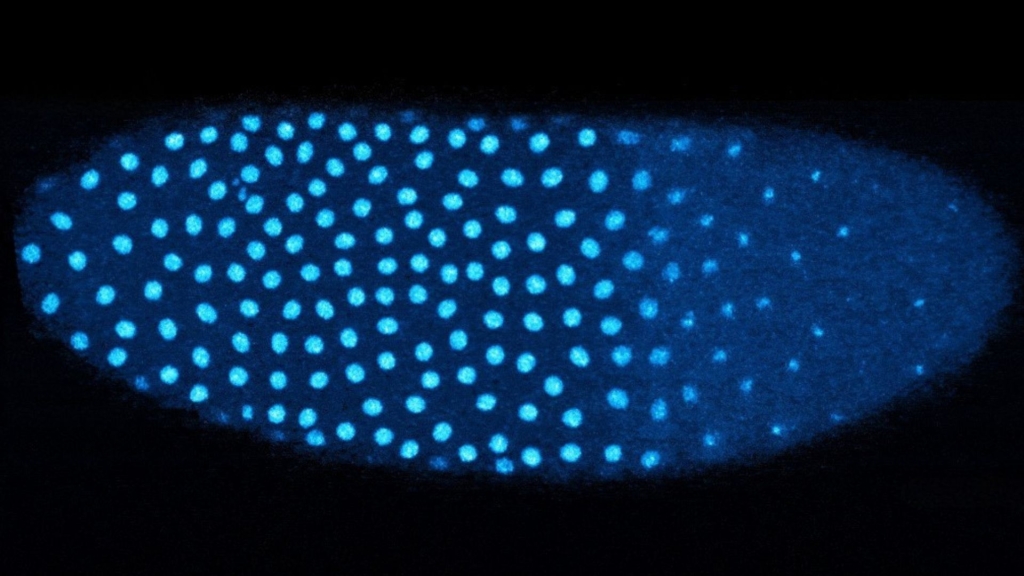

To track changes in the levels of H3 and H3.3, the researchers utilized fluorescently tagged histones. Their findings indicated that the amount of H3 decreases with each division, while levels of H3.3 rise. This shift is particularly pronounced in regions of the embryo where nuclei are densely packed.

The study also revealed that embryos lacking the ability to evenly distribute their nuclei exhibited higher levels of H3.3 in crowded regions, while areas with fewer nuclei did not experience the same transition. This suggests that the embryo’s environment plays a crucial role in determining gene activation.

Looking ahead, the research team plans to delve deeper into the role of H3.3 in genome activation. Bhatt expressed a keen interest in identifying the specific regions of the genome where H3.3 is incorporated during early cell cycles and the genes it activates.

Amodeo expressed pride in her team, noting the contributions of undergraduate students Madeleine Brown and Aurora Wackford, who co-authored the paper. Brown is currently pursuing a PhD at Cornell University, while Wackford continues her studies at Dartmouth.

This research not only enhances the understanding of embryonic development but also offers potential insights into broader biological phenomena, including cancer and aging, thereby underscoring the relevance of basic biological research to human health.