Radio astronomy is facing a significant challenge due to radio frequency interference from satellites. A recent study led by researchers at the CSIRO’s Astronomy and Space Science division has provided crucial insights into the extent of this interference from geostationary satellites positioned at approximately 36,000 kilometers above Earth.

The focus of this research was to investigate whether these distant satellites, which remain fixed relative to the Earth’s rotation, are leaking unintended radio emissions that could disrupt astronomical observations. Using archival data from the GLEAM-X survey captured by Australia’s Murchison Widefield Array in 2020, the team analyzed radio frequencies between 72 and 231 megahertz, a range critical for the upcoming Square Kilometer Array.

Key Findings on Satellite Emissions

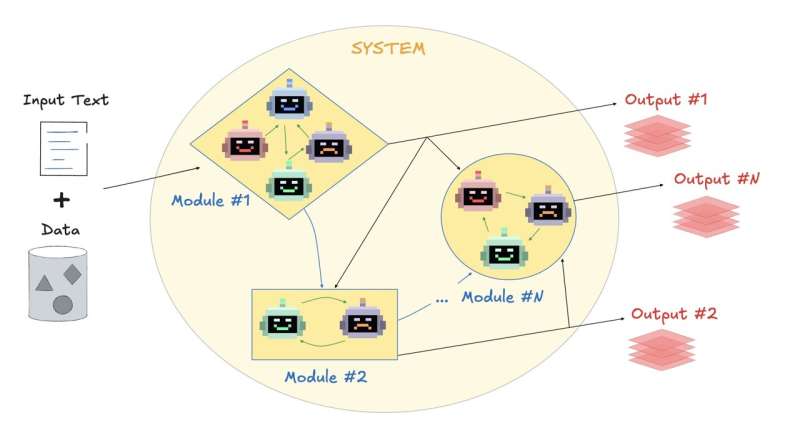

Over the course of a single night, researchers tracked up to 162 geostationary and geosynchronous satellites, stacking images based on their predicted positions to detect any radio emissions. The findings indicate that the majority of these satellites remain undetectable by radio telescopes within the specified frequency range.

For most satellites, the study established upper limits of emissions at less than 1 milliwatt of equivalent isotropic radiated power in a bandwidth of 30.72 megahertz. Impressively, the best limits reached as low as 0.3 milliwatts. Only one satellite, Intelsat 10–02, showed potential emissions at around 0.8 milliwatts, which is still significantly lower than typical emissions from low Earth orbit satellites that can radiate hundreds of times more power.

The distance and geometry of geostationary satellites play a critical role in determining the impact of their emissions. Positioned ten times further from Earth than the International Space Station, any emissions from these satellites diminish considerably by the time they reach ground-based telescopes.

Future Implications for Radio Astronomy

The methodology employed in this study involved pointing telescopes near the celestial equator, allowing satellites to remain in view for extended periods. This strategy enabled the detection of even intermittent emissions, an approach that will be especially important as the Square Kilometer Array becomes operational. The array promises to be significantly more sensitive than existing instruments in the low frequency range.

As satellite constellations proliferate and radio telescopes become increasingly sensitive, the pristine radio environment that astronomers have historically relied upon is at risk. Even satellites designed to avoid certain protected frequencies may inadvertently leak emissions through various systems.

For the moment, geostationary satellites appear to be largely respectful neighbors in the low frequency radio spectrum. The research provides a vital baseline for predicting and mitigating future radio frequency interference, but the evolving landscape of satellite technology raises questions about whether this will continue to be the case.

The study, titled “Limits on Unintended Radio Emission from Geostationary and Geosynchronous Satellites in the SKA-Low Frequency Range,” is published on the arXiv preprint server, underscoring the importance of ongoing research in safeguarding the future of radio astronomy.