Recent research suggests that cosmic rays from nearby supernovae could significantly contribute to the formation of Earth-like planets. A team led by Ryo Sawada, an astrophysicist at the Institute for Cosmic Ray Research at the University of Tokyo, has explored how these high-energy particles may play a role in creating the conditions necessary for rocky planets similar to Earth.

For decades, scientists have theorized that the early solar system was enriched with short-lived radioactive elements, particularly aluminum-26, ejected from a supernova explosion. This radioactive material is believed to have played a critical role in the development of planets by heating young planetesimals, which in turn caused them to lose water and other volatile substances.

Despite this prevailing theory, Sawada noted a significant challenge: the classic “injection” scenario requires precise conditions for a supernova to impact the protoplanetary disk effectively. The supernova must be close enough to deliver radioactive material but not so close as to destroy the disk itself, making the formation of Earth seem reliant on an exceedingly rare event.

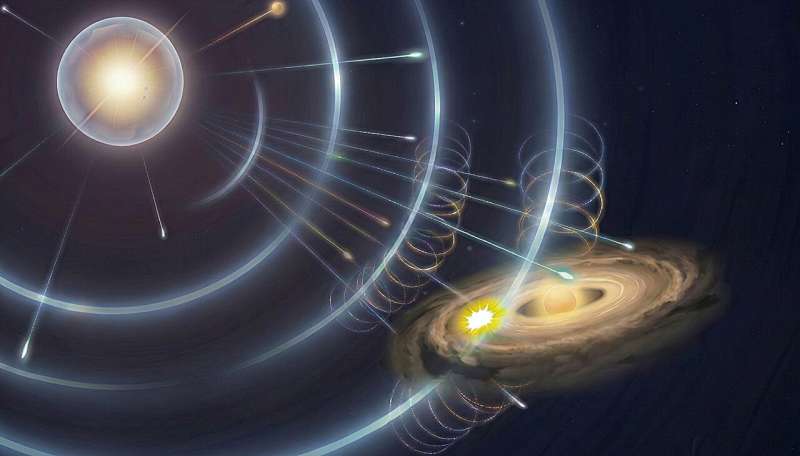

In light of this, Sawada and his colleagues began considering a different perspective. They proposed that the young solar system may not only have received material from supernovae but could also have been immersed in a bath of cosmic rays. Their recent study, published in Science Advances, utilized numerical simulations to investigate this hypothesis.

The results were striking. The interaction between cosmic rays and the protosolar disk can trigger nuclear reactions that generate short-lived radioactive elements, including aluminum-26. This mechanism proved effective at distances of approximately one parsec from a supernova, a distance often found in star clusters. Such findings suggest that the protosolar disk could remain intact without reliance on a highly improbable injection event.

Cosmic-ray bath is the term used to describe this new understanding. It offers a more universal explanation for the formation of Earth-like planets. Many sun-like stars form in clusters, which typically harbor massive stars that eventually explode as supernovae. As a result, if cosmic-ray baths are common in these environments, the thermal histories that shaped Earth might also be prevalent among many sun-like stars.

The implications of this research extend beyond merely understanding Earth’s formation. If encounters with supernovae are rare, water-depleted rocky planets like Earth could be considered exceptional. Conversely, if cosmic-ray immersion is sufficient and commonplace, then the conditions that contributed to Earth’s formation may exist around a significant number of sun-like stars.

Sawada is careful to note that their findings do not imply that supernovae guarantee the existence of habitable planets. Numerous factors still play a vital role, including the lifetime of the protoplanetary disk, the structure of star clusters, and the dynamics of stellar evolution.

Ultimately, the study emphasizes the interconnected nature of astrophysical processes. Cosmic-ray acceleration, typically associated with high-energy astrophysics, emerges as a crucial factor in planetary science and the study of habitability. As Sawada explained, understanding the origins of Earth-like planets may lie in recognizing the importance of previously overlooked phenomena.

This research not only contributes to the field of astrophysics but also prompts a reevaluation of how scientists approach the formation and evolution of planetary systems. The study illustrates the potential for further exploration into the connections between cosmic events and the development of worlds capable of supporting life.