Earth’s magnetic field has been instrumental in transporting tiny particles from our atmosphere to the moon over billions of years, according to a new study from the University of Rochester. This groundbreaking research sheds light on the mysterious gases found in lunar soil samples collected during the Apollo missions, suggesting that the moon may serve as a long-term archive of Earth’s atmospheric history.

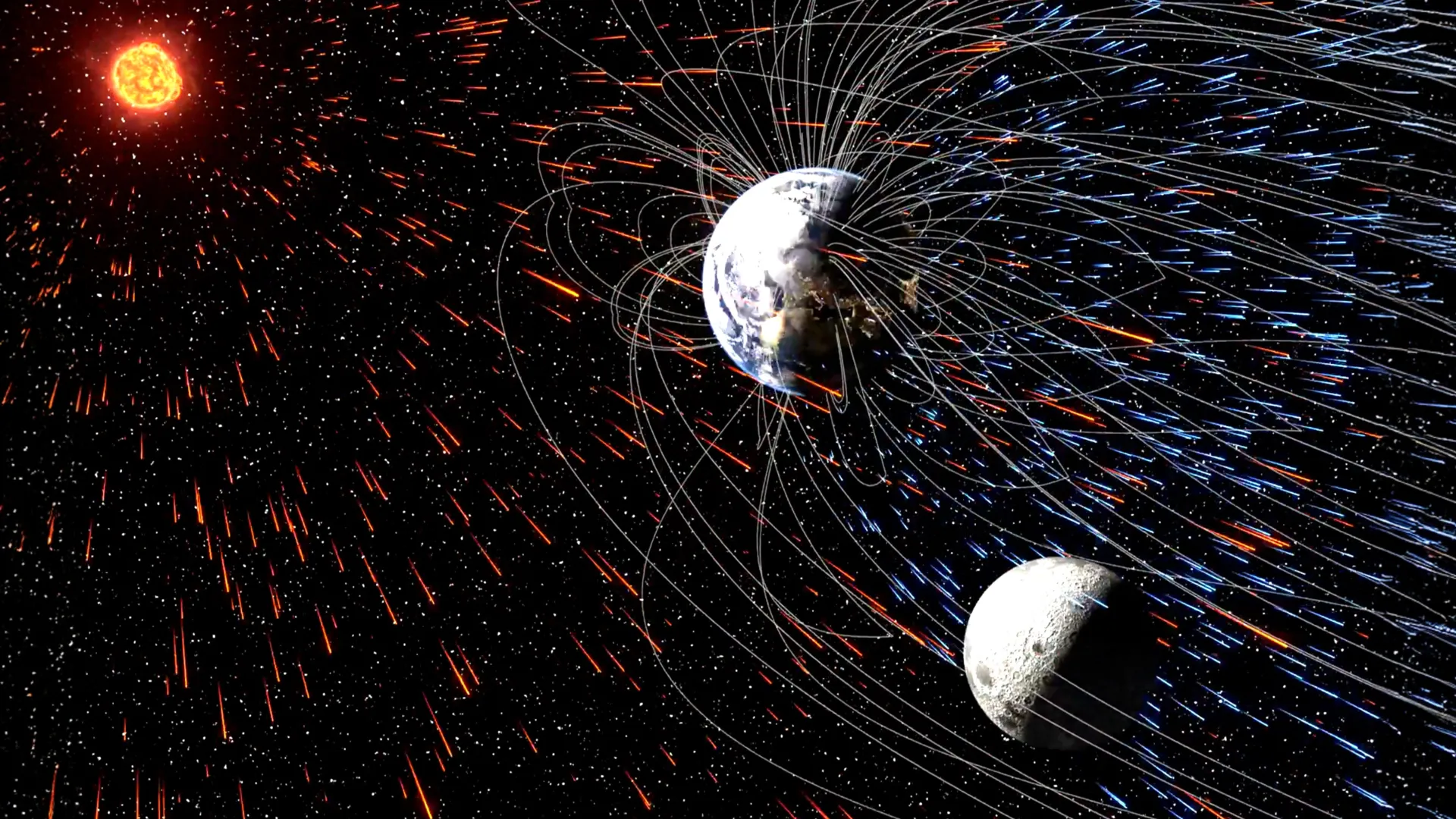

The study, published in Nature Communications Earth and Environment, reveals that rather than repelling particles, Earth’s magnetic field can funnel them along invisible lines extending to the moon. This process has enabled a slow but steady delivery of atmospheric materials to the lunar surface, raising intriguing possibilities for future lunar exploration and resource utilization.

For years, scientists have been puzzled by the presence of volatile substances such as water, carbon dioxide, helium, argon, and nitrogen found in lunar regolith. While some of these materials are known to originate from the solar wind, the quantities discovered, particularly nitrogen, exceed what solar wind alone could account for. A 2005 hypothesis from researchers at the University of Tokyo suggested these volatiles came from Earth’s atmosphere, occurring before the planet developed its magnetic shield.

The Rochester research team, led by Eric Blackman, a professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy, took a different approach. They employed advanced computer simulations to investigate how particles could travel from Earth to the moon under different conditions. The study’s co-authors included graduate student Shubhonkar Paramanick and professor John Tarduno.

By simulating two scenarios—one representing an early Earth without a magnetic field and another depicting modern Earth with a strong magnetic shield—the researchers discovered that particle transfer to the moon is significantly more effective under current conditions. Modern solar wind can dislodge charged particles from Earth’s upper atmosphere, which then follow the magnetic field lines to intersect the moon’s orbit. This mechanism allows a consistent, albeit slow, influx of Earth’s atmospheric materials to the lunar landscape.

The implications of this research extend beyond understanding lunar geology. The findings suggest that lunar soil may contain a historical record of Earth’s atmosphere, providing valuable insights into the evolution of Earth’s climate, oceans, and life over billions of years. Furthermore, the presence of useful volatiles could support long-term human habitation on the moon, reducing reliance on supplies shipped from Earth.

Paramanick noted, “Our study may also have broader implications for understanding early atmospheric escape on planets like Mars, which lacks a global magnetic field today but had one similar to Earth in the past.” This insight could help scientists comprehend how atmospheric processes influence planetary habitability across different epochs.

Funding for this research was provided by NASA and the National Science Foundation, highlighting the importance of continued exploration and understanding of celestial bodies in our solar system. As scientists delve deeper into the moon’s geological history, they may uncover not only remnants of Earth’s past but also resources that could pave the way for future lunar endeavors.