A comprehensive study led by Dr. Yuchen Tan reveals that the ancient settlement of Jiahu in Henan Province, China, not only survived the abrupt climatic event known as the 8.2 ka event but also experienced significant social transformation. The research, published in the journal Quaternary Environments and Humans, challenges the prevailing narrative that categorizes this climate event as universally catastrophic for all populations across the North China Plain.

The 8.2 ka event, which occurred approximately 8,200 years ago, was characterized by sudden cooling and drying, resulting from the collapse of the Laurentide ice sheet in North America. This collapse disrupted climate systems globally, including a notable shift in the Intertropical Convergence Zone, adversely affecting regions dependent on the East Asian Summer Monsoon. Many surrounding settlements faced significant turmoil, with evidence of widespread abandonment and disruption. In contrast, Jiahu demonstrated resilience and adaptation to these challenging conditions.

Understanding Jiahu’s Resilience

To investigate how Jiahu managed to endure, Dr. Tan and colleagues employed resilience theory frameworks, specifically the Baseline Resilience Indicator for Communities (BRIC). Initially developed to assess modern communities’ responses to natural disasters, the BRIC model was adapted to evaluate archaeological indicators of resilience. Dr. Tan emphasized the importance of translating these principles to ancient contexts, stating, “Resilience is a universal concept. Even though ancient societies are very different from modern towns, they also needed to reorganize, redistribute labor, strengthen cooperation, and adjust their use of resources when facing sudden change.”

The researchers analyzed archaeological evidence from three distinct occupation phases at Jiahu: Phase I (9.0–8.5 ka BP), Phase II (8.5–8.0 ka BP), and Phase III (8.0–7.5 ka BP). During Phase II, which coincided with the 8.2 ka event, the study found significant increases in burial practices, surging from 88 burials in Phase I to 206 in Phase II. This rise likely reflects both heightened mortality rates and an influx of migrants seeking refuge from the harsher conditions affecting neighboring areas.

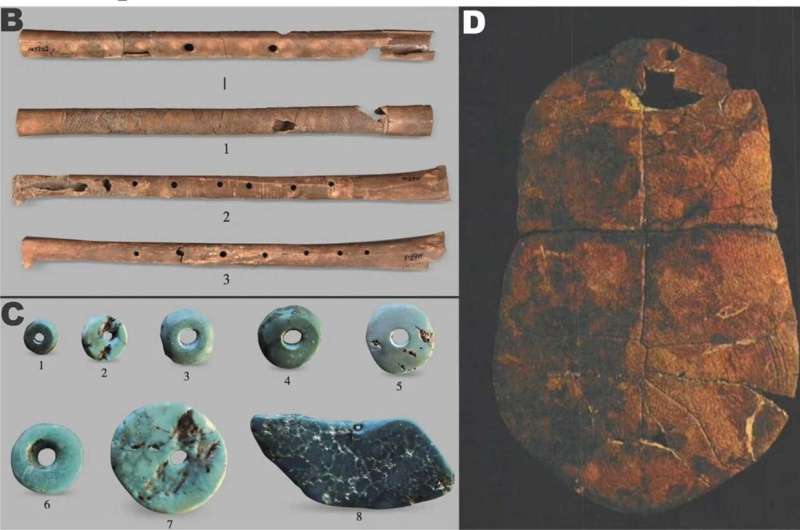

In addition to changes in burial numbers, the research indicated that burial practices became more standardized, and grave goods increased significantly. These trends suggest the emergence of social stratification and wealth disparities within the community. Analysis of skeletal remains pointed to a more defined division of labor, with males exhibiting higher rates of osteoarthritis, which may indicate involvement in physically demanding activities.

Transformation and Adaptation

The influx of migrants and the enhanced division of labor likely contributed to Jiahu’s increased workforce, enabling the settlement to secure food and manage challenges resulting from the 8.2 ka event. By the time Phase III began, burials decreased to 182, and grave goods became less common. This shift indicates an active reorganization and transformation within the community as it adapted to the evolving environmental landscape.

Dr. Tan noted that the eventual decline of Jiahu was not a direct result of the 8.2 ka event but rather a consequence of subsequent climatic fluctuations, which led to increased flooding. “After Phase III, the Jiahu settlement faced frequent climatic fluctuations, which further triggered flooding and finally led to the decline of the Jiahu culture,” Dr. Tan explained. The alterations in the environment fundamentally changed the habitat, rendering the settlement unsustainable.

This study underscores the remarkable adaptability of ancient communities when confronted with environmental crises. By applying the BRIC model to archaeological contexts, researchers can gain valuable insights into how human societies reorganize in response to abrupt climatic changes. The findings from Jiahu provide a nuanced perspective on resilience during one of the most significant climatic events of the Holocene, highlighting the complexities of human adaptation rather than a simplistic narrative of destruction.