A breakthrough in solar sail technology has emerged from researchers at the University of Pennsylvania. In a recently published preprint paper, scientists Gulzhan Aldan and Igor Bargatin introduce a novel technique to enhance the maneuverability of solar sails using an ancient Japanese art form known as kirigami. This innovative approach addresses a long-standing challenge in the field of solar propulsion: how to effectively change the direction of a solar sail without relying on traditional propellant methods.

Solar sails offer a significant advantage over conventional propulsion systems by utilizing sunlight as their primary source of energy. Unlike traditional sailing, where a captain adjusts sails to catch the wind, solar sails have historically struggled with steering due to the absence of rudders when sailing on light. The authors’ research presents kirigami as a solution to this issue, enabling the sails to turn by altering their shape through controlled buckling.

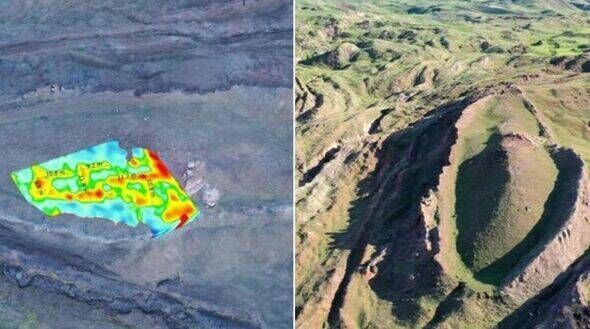

The kirigami technique involves making specific “cuts” in the sail’s material, which is typically made from aluminized polyimide film. These cuts allow the material to buckle and form a three-dimensional shape, tilting various segments of the sail in response to sunlight. This transformation effectively creates thousands of tiny mirrors that reflect light at different angles. According to the principles of conservation of momentum, this reaction propels the sail in an opposite direction to the light’s reflection.

Traditionally, solar sails have relied on several methods for turning, including reaction wheels and tip vanes. Reaction wheels, while effective, require propellant and add significant weight, limiting the sail’s operational capabilities. More recent developments like tip vanes introduce mechanical complexity and are prone to failure. The most advanced systems, such as Reflectivity Control Devices (RCDs), involve liquid crystal panels that adjust their reflective properties but depend on a continuous power supply, draining batteries over time.

In contrast, the kirigami sail requires minimal energy, utilizing servo motors that are power-efficient and only draw energy when in operation. Although some power is still needed to facilitate the buckling process, the overall energy consumption is significantly lower than that of existing systems.

To validate their method, Aldan and Bargatin conducted simulations using COMSOL, a widely recognized physics simulation software. They performed ray tracing experiments to analyze the forces acting on the sail under various conditions of buckling and solar angles. The experiments indicated that even a small force—measured at 1 nN per Watt of sunlight—could effectively turn a small solar sail and its payload over time.

The researchers also conducted a physical experiment by cutting film and placing it in a test chamber. They shone a laser on the film while applying tension, observing how the laser beam moved across the chamber walls. The results aligned closely with their predicted angles of incidence for each strain level, confirming the functionality of the kirigami technique.

This advancement could considerably impact the future of solar sailing by reducing the energy and propellant costs associated with directional changes. Despite the promise of kirigami sails, numerous competing technologies aim to achieve similar results. The field lacks extensive experimental missions to test these technologies, suggesting that it may take time before kirigami sails are deployed in space.

As research continues, the potential for this innovative navigation method to transform solar sailing remains significant. When implemented, it is expected that the resulting sails will not only be effective in propulsion but will also showcase a unique and visually striking design.