Research from Cornell University has revealed significant insights into how soil microbes affect carbon dynamics during the decomposition of plants. Published on December 10, 2023, in the journal Nature Communications, the study indicates that soil molecular diversity increases during the first month of microbial decomposition before subsequently plateauing and declining.

Understanding the role of soil microbes is crucial to addressing climate change, as soils hold approximately three times more carbon than the atmosphere and all plants combined. Senior author Johannes Lehmann, a professor in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, emphasized the importance of this research: “This is a hugely important question: can we lose less carbon from soil, or can we even increase our soil carbon stocks, which will help regulate CO2 in the atmosphere?”

The study’s lead author, Rachelle Davenport, Ph.D. ’24, who previously worked in Lehmann’s lab, noted that even small changes in soil organic carbon can significantly impact atmospheric CO2 levels. The research involved a collaborative effort, with 11 co-authors from seven institutions across six U.S. states and the Netherlands.

For decades, scientists held the belief that soil organic carbon accumulated solely due to recalcitrant plant materials. However, a groundbreaking study published in 2011 by Lehmann and co-authors challenged this notion, showing that complex ecosystem interactions, including those with soil microorganisms, play a vital role in carbon storage.

Lehmann and his team proposed in 2020 that higher molecular diversity within soils could limit decomposition rates, promoting greater carbon retention. This latest paper offers the first empirical evidence supporting the idea that plant decomposition initially increases molecular diversity in soils, peaking at 32 days before declining.

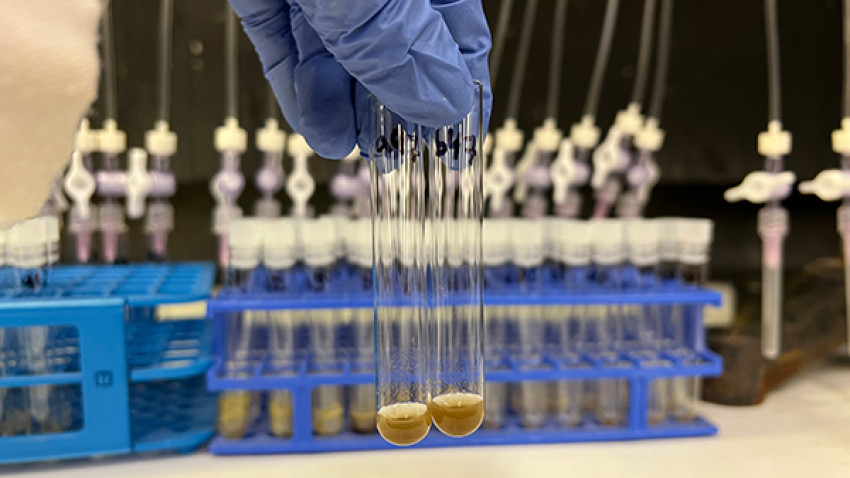

To measure molecular diversity, the researchers extracted organic matter with water and analyzed the compounds using high-resolution mass spectrometry. Notably, this study marks the first use of “18O heavy water” to trace changes in soil molecular composition as a result of microbial activity. Traditional methods often involve feeding microbes simple sugars, which can skew results. Davenport explained, “When you trace activity via carbon, you usually feed microbes glucose… that affects their metabolism and you’re not really accurately measuring microbial activity.”

The collaboration with the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory in Richland, Washington, was instrumental in developing this innovative method. Funding for the research included grants from the U.S. National Institute for Food and Agriculture, the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, and two Cornell grants.

Going forward, researchers aim to explore whether greater diversity among soil molecules, microorganisms, and minerals can enhance carbon storage. If successful, this could lead to the development of strategies to support diversity through farm and forest management practices. Lehmann concluded, “We still have much to learn, but this is one important piece of the bigger puzzle.”

The findings underscore the complex interplay between soil ecosystems and climate dynamics, highlighting the potential for nuanced approaches to carbon management in the face of climate change.