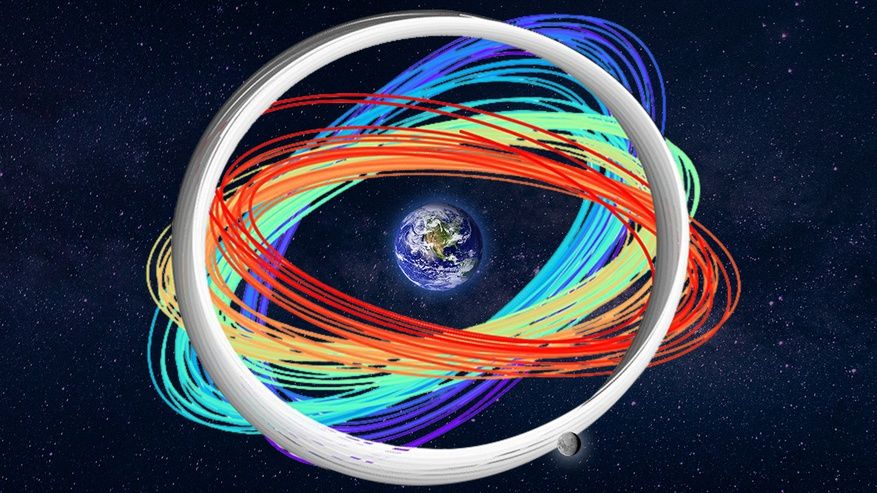

The increasing density of human-made objects in Earth’s orbit has prompted researchers at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) to develop a groundbreaking method for predicting satellite trajectories. With over 45,000 objects currently orbiting our planet, the risk of collisions is rising sharply, especially with numerous new missions scheduled for 2026. This innovative approach utilizes a model of one million orbits, aiming to enhance safety in space.

The researchers focused on cislunar space, the region between Earth and the Moon. They employed an open-access database along with substantial processing power from the lab’s supercomputers to simulate the behavior of these orbits over a six-year period. The challenges posed by space debris are becoming increasingly apparent, particularly with the growing number of satellite launches and planned lunar missions.

According to LLNL scientist Denvir Higgins, the extensive data generated from modeling a million orbits allows for in-depth analysis through machine learning applications. “You can try to predict the lifetime of the orbit, try to predict stability or do anomaly detection to see if an orbit is moving in a strange way,” Higgins explained. This capability is critical as it provides insights into how long satellites might remain operational and safe from collisions.

The simulation results revealed that approximately half of the modeled orbits maintained stability for at least one year, while just under 10% remained stable throughout the entire six years. Fellow LLNL scientist Travis Yeager noted, “If you want to know where a satellite is in a week, there’s no equation that can actually tell you where it’s going to be. You have to step forward a little bit at a time.”

Running the simulations required immense computing resources, amounting to 1.6 million CPU hours—equivalent to more than 182 years of processing time on a single computer. However, thanks to the power of the lab’s Quartz and Ruby supercomputers, the researchers completed the simulations in just three days.

This research holds significant promise for the future of satellite navigation. LLNL officials emphasized that as more countries launch satellites without coordinated efforts, this modeling approach could become a vital tool for identifying busy intersections in space. The results of this study not only contribute to addressing collision risks but also pave the way for safer space exploration in an increasingly congested orbital environment.